As the temperature drops and winter sets in, many people feel the familiar signs of the season: chilly fingers, dry skin and that sluggish sensation that can creep in during colder months. But what is happening on a deeper, cellular level? While we tend to think of cold weather as just a surface discomfort, it affects the body down to the cell.

Holly Chen, Ph.D., assistant professor at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, Marnix E. Heersink School of Medicine, Department of Cell, Developmental and Integrative Biology, discusses how cells in the body sense the cold, and ways to help support cells in the winter.

The body’s response to the cold

When exposed to cold, the human body quickly switches into survival mode. It prioritizes heat retention and protecting vital organs, often by narrowing blood vessels in the skin and extremities. This means cells in peripheral tissues can experience colder temperatures and reduced blood flow, which alters how they function.

As the temperature drops and winter sets in, many people feel the familiar signs of the season: chilly fingers, dry skin and that sluggish sensation that can creep in during colder months. But what is happening on a deeper, cellular level?One of the most noticeable effects is a slowdown in cellular activity. Enzymes, the proteins that drive energy production and other cellular processes, are sensitive to temperature. In areas where tissue temperatures drop, these enzymes work less efficiently.

As the temperature drops and winter sets in, many people feel the familiar signs of the season: chilly fingers, dry skin and that sluggish sensation that can creep in during colder months. But what is happening on a deeper, cellular level?One of the most noticeable effects is a slowdown in cellular activity. Enzymes, the proteins that drive energy production and other cellular processes, are sensitive to temperature. In areas where tissue temperatures drop, these enzymes work less efficiently.

On a microscopic level, cold changes the structure of the cell membranes, which are thin, fatty layers that protect cells and control what enters and leaves. At lower temperatures, these membranes become less fluid and more rigid, which can affect how cells transport nutrients, remove waste and communicate. In animals that do not regulate their body temperature as tightly as humans, such as fish or insects, this membrane stiffening is a major survival challenge. For people, the effects are most noticeable in tissues that are directly exposed to cold.

Protecting cells

“The best way to protect cells from cold weather is not all that different from how we bundle up ourselves,” Chen said. “Our bodies are completely made of cells, and in a sense, cells need blankets just as we do on a cold day.”

So how do the cells create their own “blanket”? One key way is by fine-tuning the makeup of their outer membranes. Cell membranes are built mainly from fats called phospholipids, with cholesterol woven in. These components work together to control how flexible or rigid the membrane is. Cholesterol in particular acts like a stabilizer. In colder conditions, it helps keep membranes from becoming too stiff, ensuring that cells can still move nutrients, remove waste and send signals effectively.

Consuming warm fluids and wearing layered clothing that insulates the torso can signal to the body that it is safe to circulate blood to the hands and feet—areas that typically feel the chill first.

Over time, cells can adjust the types of fats in their membranes, favoring those that stay more flexible in the cold. However, cells cannot do it all on their own. What is done at the whole-body level directly supports what is happening at the cellular level.

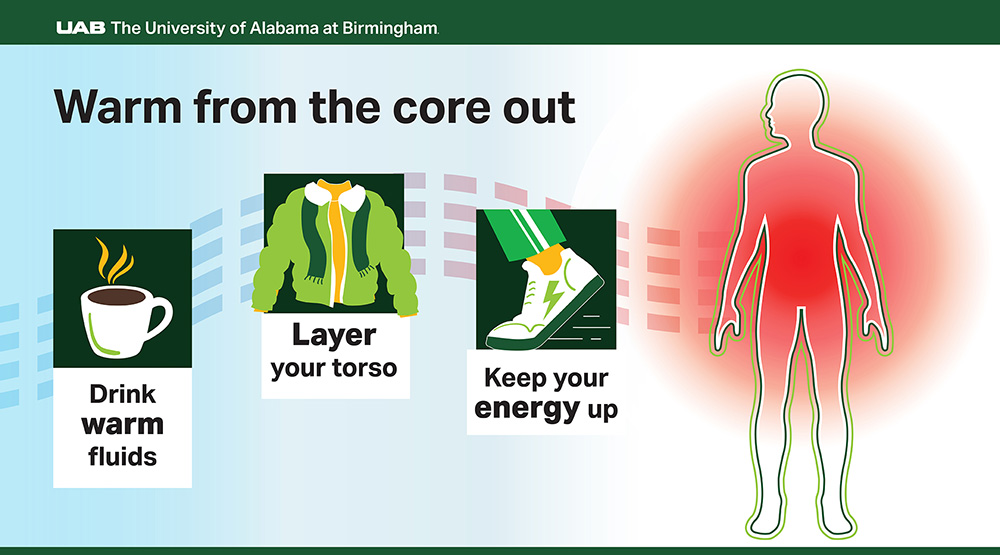

A simple trick: Warm from the core out

Protecting cellular health during colder months involves practical strategies. One effective approach is to prioritize warming the body’s core rather than focusing solely on the extremities.

Consuming warm fluids and wearing layered clothing that insulates the torso can signal to the body that it is safe to circulate blood to the hands and feet, areas that typically feel the chill first.

This improves peripheral warmth and helps sustain energy levels and supports immune function, both of which may decline with prolonged cold exposure.

Chen says understanding how cold weather affects cells is a reminder that staying warm is not just about comfort; it is about giving our bodies, and every cell within them, the support they need to thrive through winter.