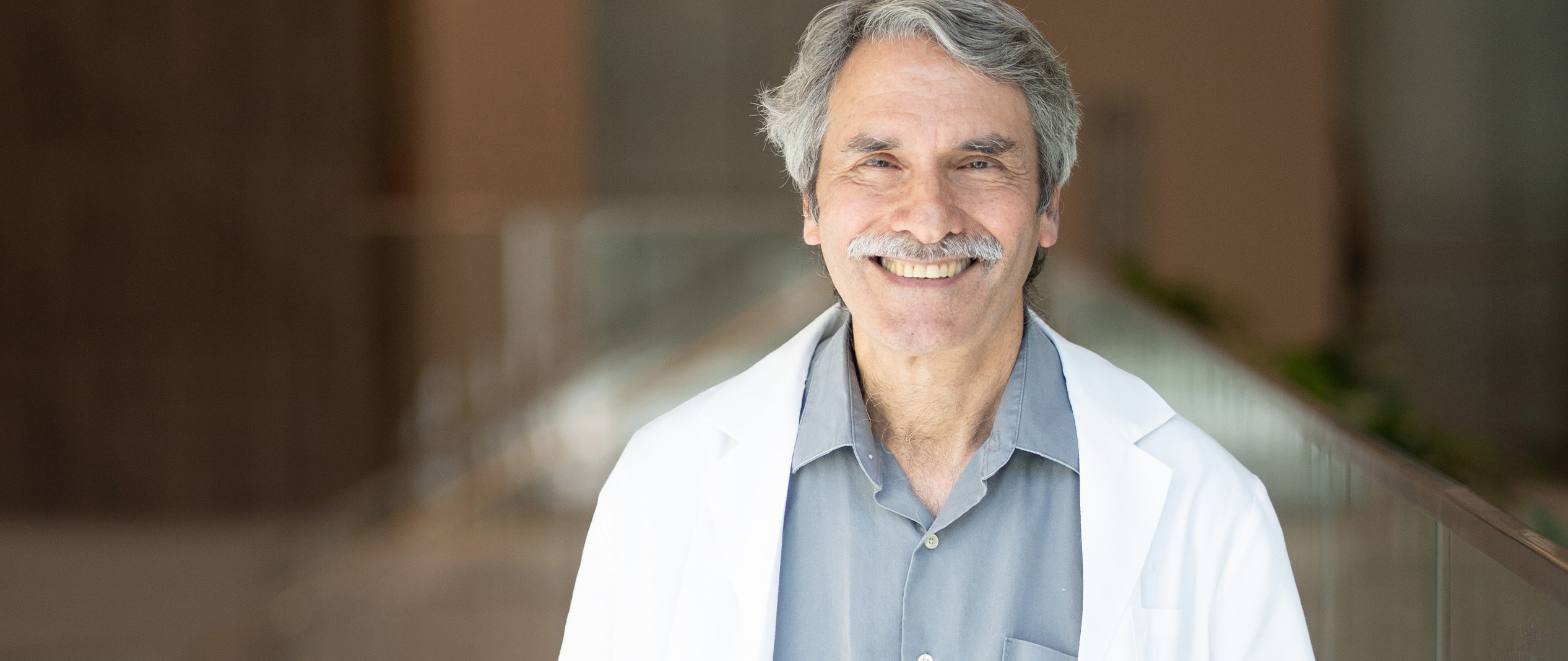

Early in his career, Michael Allon, M.D., professor in the UAB Division of Nephrology, Department of Medicine, noticed that the prevailing wisdom concerning vascular access did not match his observed experience.

Hemodialysis is the process of filtering and removing waste and excess fluids from the body, usually when the patient’s kidneys cannot do so because of disease or dysfunction. A needle or catheter is used to draw blood out of the patient's body and into a hemodialysis machine. The blood is then passed through a dialyzer, which separates waste products and excess fluid from the blood. The cleaned blood is returned to the patient's body through another needle or catheter.

As a nephrologist, Allon knew that successful dialysis requires a reliable method to withdraw blood from the patient’s circulation (“vascular access”). What Allon questioned was the best type of vascular access for dialysis. “In the 1990s, the National Kidney Foundation guidelines said that the best type of vascular access was a fistula, where the surgeon directly connects an artery to a vein in the arm,” Allon explained. “Grafts, where the surgeon takes a piece of plastic tubing and inserts one end into the artery and the other end into the vein, were considered a poor second choice. However, the more I reviewed the standards, the more I questioned those recommendations. What I found in my clinical practice was not consistent with what was recommended.”

When those vascular access recommendations were made in the 1990s, Allon observed, only about 25 percent of dialysis patients were using a fistula; most patients had a graft. Also, fistulas were mostly put in an extremely specific population of dialysis patients.

When those vascular access recommendations were made in the 1990s, Allon observed, only about 25 percent of dialysis patients were using a fistula; most patients had a graft. Also, fistulas were mostly put in an extremely specific population of dialysis patients.

“Those patients were young, they were male, and they did not have a lot of medical conditions. In that specific population, the fistula worked very well. The problems started when we accepted those guidelines and started saying, ‘Well, we should put fistulas in everyone, right? Why only 25 percent?’ That is where we ran into problems.”

Allon and his collaborators soon found that in older patients, women, and patients with more severe vascular disease, a higher proportion of fistulas failed to mature, or expand to a size usable for dialysis.

“When all this was considered, we found that approximately 40 percent of fistulas did not mature. That is where I started trying to understand what the issues were and how we could improve the outcomes,” Allon said. “By putting a graft rather than a fistula in specific populations, you end up using the right type of access in each patient.”

This "right access in the right patient" practice spearheaded by Allon resulted in fewer procedures to maintain vascular access and fewer dollars spent by the healthcare system. Now, the revised 2019 recommendations are to place the right access in the right patient at the right time for the right reason, a vast change from the earlier “fistula first” guidelines.

Allon’s research challenging longstanding assumptions about vascular access in hemodialysis was recognized in 2025 with the Belding H. Scribner Lifetime Achievement Award from the American Society of Nephrology. “Do not be afraid to challenge the prevailing status quo of what physicians believe. Wherever the research leads you, do not be afraid to pursue that and to publicize that,” Allon said. “If you are right, it can change how people in the entire specialty perceive and manage that problem, and the patients benefit.”

Read other stories